Viewing Education as a System I

Note: The aim of this nine-part series is to define and describe the basic structure and components of a system. This is the eighth post in the series, which is excerpted from Chapter 4 of my recently published book, Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools.

W. Edwards Deming’s teachings are most widely known in industry and government. However, his teachings and principles apply to educational institutions, which of course, is the very point of Win-Win. He taught the Japanese, and later American companies that would listen, to adopt a systems thinking perspective.

The key point to what Dr. Deming called Appreciation for a System in the manufacturing setting is that most of the differences observed in workers’ performance are caused by sources of variation within the production system itself and not by the workers. The skills and efforts of workers do impact the outputs of the manufacturing process, but are far less significant than the effect of the system on those outputs. Once management began to look outside the walls of their factories to external suppliers and customers as integral parts of their manufacturing system, they discovered numerous opportunities for improving quality, productivity, and competitive position. When they looked inside the walls of their own organization, they also found vast opportunities for improvement.

Before I go any further with the analogy between manufacturing and schools, I want to explicitly make a pre-emptive strike to objections from educators about the comparison between production work and educating students. The comparison between business and education settings have been made many times over the last few decades, often in objectionable ways. However, the analogy that I am going to outline is useful, and if you stick with me, is the exact opposite of treating teachers and students like inanimate products or widgets within an education production system. In fact, the framework I’m about to present is the very one that most shifted my own thinking regarding how we need to rethink our attempts at school improvement. As I dive into this example, it will be useful to take another look at Figure 1 below, which we first saw in the second post in this series, in order to think through the insights that can be extrapolated from applying the systems perspective to schools.

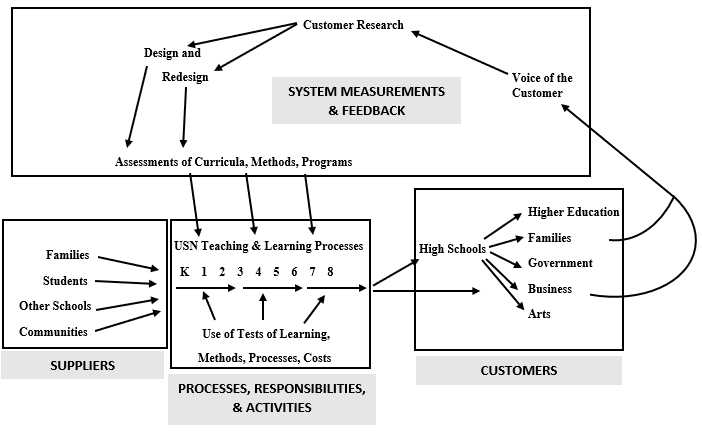

Figure 1. USN Systems View with Four Labels

Figure 1 illustrates K-12 education as a system that produces knowledge and skills. An important distinction is that what is being produced is high-quality learning (i.e., skills and knowledge) and not the students themselves. Like the performance of production workers, most of the differences in achievement and test scores at the individual student level are caused by sources of variation embedded within the complex and dynamic system in which they are being educated. Peter Scholtes gave us a very useful way to think about this dynamic:

The old adage, "If the student hasn't learned, the teacher hasn't taught" is not true or useful. Instead a much more useful characterization is, "If the learner hasn't learned, the system is not yet adequate.”[1]

By taking the systems view, numerous opportunities for improvement that were hidden from view nearly jump off the page. This could include a method for regularly collecting feedback from high school graduates 5-10 years after graduation. Think of the power of asking graduates from your education system the following question: Did we make a difference in your life? Alumni answers to this question will let you know the true purpose of your organization, and if you are fulfilling the mission statement on the wall.

It would be obvious and non-controversial to most educators to highlight the important role that parents and families play in the education system. If you look at the right side of Figure 1, families are customers of the K-12 education system just like higher education institutions, local businesses, and society at large. However, families also show up on the left side of the model as suppliers. In the role of customer, and as I’m certain educators have heard, families may regularly ask their child’s teachers, “What have you done for us lately?” On the flip-side though, and this would very likely be much more controversial in most places, the K-12 education system also should be able to ask of its suppliers, “What have you done for us lately?”

The point isn’t to assign blame, but rather that no one within the system gets to take a passive role. When we define a school system as the employees that work within the district, you lose this perspective. Taking a systems view helps everyone to recognize that they have a stake in making our education institutions as strong as possible.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter school campuses in Columbus, Ohio. He is also the author of the newly released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschools.org.

Notes

1. Peter Scholtes, The Leader’s Handbook: A Guide to Inspiring Your People and Managing the Daily Workflow (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998), 36.