Two Types of Knowledge

I have a challenge for you. Get a piece of paper and a pen, and list examples of successful improvement efforts you’ve led in your school system before reading any further.

Now that you have your list, let’s outline a clear definition for improvement. Improvement results from fundamental changes you’ve made to some component of your system that do the following:

alter how work or activity is done or the make-up of a tool;

produce visible, positive differences in results relative to historical norms; and

have a lasting impact.

Go back to your list and cross out any examples that don’t meet all three conditions. If you’re like me, you likely have very few items left on your list. My thesis is that many of us have long relied on a single source of knowledge without realizing that there is another source that is at least as equally important to our ability to improve schools.

Subject-Matter Knowledge

When we as educational leaders are confronted with a problem, we typically assemble a school or district team to attempt to improve it. The team relies on the expertise they’ve acquired across their careers as classroom teachers, building administrators, and district level leaders. Let’s call this subject matter-knowledge. It includes skills like data-driven instruction, curriculum planning, and leading professional development, among many other activities.

Subject-matter knowledge is critical for developing changes that result in improvement. While an obvious necessity, this type of knowledge alone is insufficient. When serving on school and district leadership teams, I often felt that I was missing an important part of the improvement picture. These are the pieces of the puzzle no amount of subject-matter knowledge provides. These puzzle pieces include:

seeing and understanding our organizations as complex systems;

knowing when and how to react to changes in important data;

understanding how to get potentially good ideas to work in our context; and

understanding the role psychology plays in improvement work.

Profound Knowledge

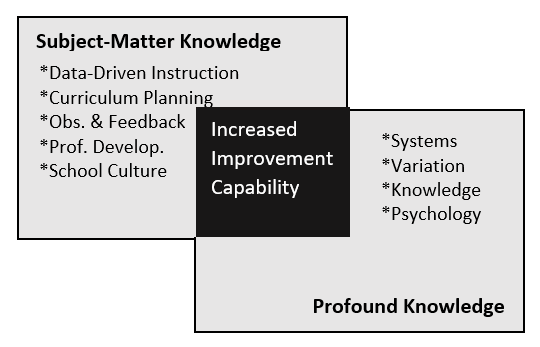

W. Edwards Deming proposed a body of knowledge he called a “System of Profound Knowledge.” Deming defined the System of Profound Knowledge as the interconnection of the theories of systems, variation, knowledge, and psychology. The ability to improve schools is enhanced when we join together subject-matter knowledge and profound knowledge in innovative ways. This interplay is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Increased Improvement Capability with Two Types of Knowledge

This second type of knowledge is little known in the education sector, but it has long been utilized in industry and healthcare. Deming described profound knowledge as four interdependent components:

Appreciation for a System

Knowledge about Variation

Theory of Knowledge

Psychology

It is a management philosophy that provides the foundation for the methods, techniques, and tools used during improvement projects. It is a way of thinking with some tools attached. A leader does not need to be eminent in the four components of profound knowledge, but they do need to understand the basic theory, their interconnectedness, and why they are necessary for school improvement efforts.

System Leaders

System leaders that are at the helm of our country’s school districts, charter management organizations, and educational nonprofits, as well as those that train these leaders in our graduate schools of education, must be aware of both subject-matter and profound knowledge. The System of Profound Knowledge can be used to guide school improvement efforts, and more broadly, to lead school systems. In Deming’s words:

The System of Profound Knowledge provides a lens. It provides a new map of theory by which to understand and optimize organizations that we work in, and thus to make contributions to the whole country.

Deming gave us a way to view our organizations that was previously unknown; a lens that gives us profound knowledge about these organizations. When we lack profound knowledge, we are more likely to be enticed by the fads of the day and the mythical improvement magic bullets. With it, we have a new map of theory by which to understand and optimize the organizations in which we work. It is through this lens that we can systematically make any number of decisions that arrive on our desk daily. When combined with subject-matter knowledge, it can be leveraged as a powerful force for change to truly make contributions to the systems we lead and in turn the country as a whole.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.