Principle 10: Eliminate Slogans, Exhortations, & Targets

Common management myths (see here and here) must be replaced by sound guiding principles. In this post, I’ll describe the tenth such principle, Eliminate Slogans, Exhortations, & Targets. It is worth noting that the 14 Principles for Educational Systems Transformation are mutually supporting, so it is important to understand all of them rather than studying them in isolation. An in-depth discussion of the full set of Principles for Transformation can be found in Chapter 3 of my recently released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools.

Principle 10: Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for educators and students that ask for perfect performance and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of teachers and students.

What is wrong with slogans, exhortations, and targets for educators and students? The main problem is that they are directed at the wrong people. They are based on the premise that teachers and students could, by simply putting in more effort, work to improve quality, productivity, and all else that is desirable. However, the slogans, exhortations, and targets do not account for the fact that most trouble within schools come from the system. Recall here one of W. Edwards Deming’s most well-known quotes, “Most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to proportions something like this: 94% belong to the system (responsibility of management), 6% special.” A primary tool for management should be the process behavior chart. It’s able to indicate which problems come from the system (responsibility of management) and which problems come from other causes.

This problem becomes particularly pernicious when exhortations of some type are deployed in a stable system with defective items. Setting goals for people to work towards seems like a good idea. However, not only is goal-setting useless in this situation, it’s often an act of desperation that has the opposite of the intended impact.

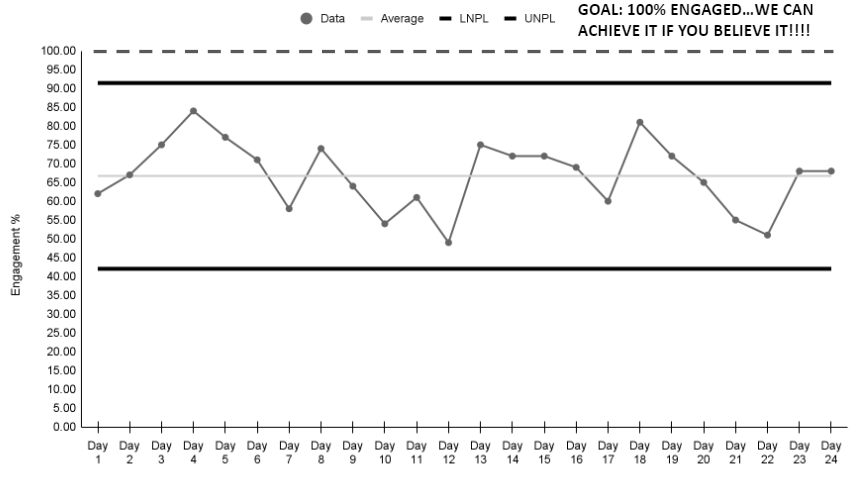

Think back to the 8th grade math engagement data discussed in my Variation is the Enemy post, which I wrote during the height of the pandemic. Imagine if the principal from this example created posters with the exhortation, “100% ENGAGED…WE CAN ACHIEVE IT IF YOU BELIEVE IT!!!” with the remote learning engagement data listed below the proclamation. The data in the poster and shown in Figure 1 shows a stable system of output with 67% average daily engagement. School leadership obviously wants to see higher engagement rates and fewer days with low rates. The problem is the exhortation is asking the teacher to do what they are unable to do. As designed, this system is not capable of achieving 100% remote learning engagement, so the effect of the goal is fear and mistrust towards leadership.

Figure 1. X Chart: 8th Grade Math Engagement Data with Goal Line

During the pandemic, better content for the poster would have been to explain to everyone in the school what the leadership is doing month-by-month to improve the remote learning engagement system. This may include strategies such as making sure that every student has access to a device and reliable internet connectivity at home and that every teacher has been trained in remote learning methods. Leadership to improve quality and productivity is completely different from exhortations to achieve a goal. Teachers would then understand that the leadership is taking some responsibility for the lack of engagement and trying to remove obstacles.

All of this talk of goal-setting is not to suggest that individuals should not set goals. You may have a goal to complete your master’s degree in the next two years. I have a goal to run a 10K in October. Goals are helpful and necessary tools for individuals. However, numerical goals set for other people without an accompanying set of methods by which to accomplish the goals have an effect opposite what is intended.

Blog Series: 14 Principles for Educational Systems Transformation

The four components of the System of Profound Knowledge work in concert to provide us with profound insights about how our organizations operate so that leaders can in turn work to optimize the whole of our systems. However, there is a step beyond simply avoiding the management myths. The next step is to be able to think and make decisions using the lens provided by the System of Profound Knowledge. This is where the core set of 14 Principles come into play. In this series, I’m describing the principles that will enable you to move from theory to practice with the Deming philosophy.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. He is also the author of the newly released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.